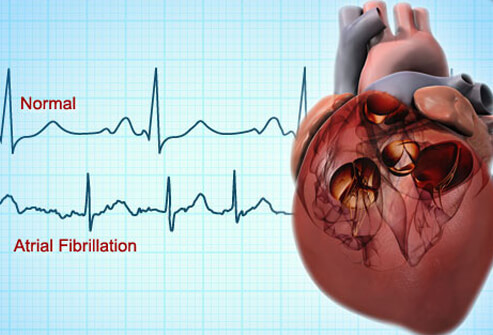

What Should I Do with My Atrial Fibrillatiion?

What causes atrial fibrillation?

Everything and nothing. Dozens of conditions can be associated with atrial fibrillation (AF), but few patients have an identifiable cause of their atrial fibrillation.

Non-cardiac causes include age, obesity, alcohol, excess caffeine, and hyperthyroidism. The older you are, the more likely you will get AF. Obesity not only put rolls of fat around your belly, it also ends up coating the heart with fat. Patients with more fat around the heart as seen on MRI scans get more AF. People who drink way too much caffeine or any amount of alcohol are also more prone to AF. Too little exercise and ironically, too much exercise in endurance athletes, can predispose to AF. President George H W Bush famously got AF while in the White House and was later found to have hyperthyroidism.

Cardiac causes. Almost every disease of the heart including hypertension, coronary disease, diseases of the heart muscle, abnormalities of the heart valves, and inflammation of the outer lining of the heart (pericarditis) can cause AF.

What is the risk of something bad happening to me?

There are two main things we worry about when patients have atrial fibrillation. The first is a weakening of the heart muscle that we call a cardiomyopathy. The second, which can be even more serious, is stroke.

Weakening of the heart muscle can occur when the heart goes very fast, in excess of 110 beats per minute, for weeks and months. The fast heartbeat is called a tachycardia, and the weakening of the heart in fast AF is called tachycardia related cardiomyopathy. Patients with this condition can fill up with fluid, a condition called congestive heart failure or CHF. Fortunately, tachycardia related cardiomyopathy will usually reverse and go away over a period of months after the heart rate is controlled.

The most feared complication of AF is a disabling stroke. Stroke in AF is caused by clot that forms in the left atrial appendage, which is like a windsock attached to the side of the left atrium. When one of these clots breaks loose, it flies out of the heart and can take a turn into the arteries that lead to the brain. The loose clot will plug up a brain artery and within a few minutes will begin to kill a smaller or larger piece of brain. If the clot is small and dissolves quickly, it only causes brief symptoms of a mini stroke (also called a TIA). If the damage is persistent, it will cause a stroke. If a patient is lucky and quickly goes to a hospital where he is given a clot busting drug like tPA, or if a neuroradiology specialist can extract the clot with a catheter, the stroke symptoms can be fully or partially relieved.

Which patients are a greatest risk of stroke?

We use a risk score to evaluate the risk of stroke. It’s called CHADSVASc. Each letter stands for a condition which has a point score that we add up to assess the total risk: C=Congestive heart failure=1 point, H=Hypertension=1 point, A=Age 65-75=1 point or Age >75=2 points, Diabetes=1 point, S=Stroke or TiA=2 points, VA=Vascular disease of the heart, legs or brain arteries=1 point, Sex Classification: Female Sex=1 point, Male Sex=0 point. If your score is 3 points, you have enough risk to require blood thinners. 2 points, not counting sex, is also enough to justify blood thinners.

Aspirin is not a good enough blood thinner for patients with these high risk scores. Traditionally we have recommended Coumadin (warfarin), but the newer blood thinners such as Eliquis, Xarelto, Savaysa and Pradaxa have many advantages over Coumadin.

What if I have a high risk score but cannot take a blood thinner?

There are some patients who can’t take a blood thinner because they have had serious bleeding episodes, or because they engage in activities like cycling or skiing that make the use of blood thinners too risky.

Nearly all clots that cause strokes in atrial fibrillation come from the left atrial appendage. The left atrial appendage is like a windsock that is attached to the body of the left atrium. If the opening to the appendage is closed off, then clots stay bottled up. The appendage can be closed off in several different ways. It can be cut off and sewn over surgically, it can be closed with an external loop of suture tied around its base or a mechanical clip, and it can be plugged with a Gortex occluder. Only Gortex occluders, called the Watchman or Amulet, have been studied extensively and approved by the FDA.

The Watchman and Amulet are inserted through a vein and deployed though a catheter without the need for surgery. There is a small risk of complications during insertion, and blood thinners are needed for several weeks after insertion. But in the long run, patients have as few strokes and far less bleeding than those on longterm blood thinners.

I feel terrible when I am in atrial fibrillation. What to do?

Most patients feel better when their heart rate is slowed down to normal, but others will feel out of sorts, tired, short of breath, and generally crummy when they are in AF. Many of these symptoms will go away after a few weeks of steady atrial fibrillation as the body compensates. But some patients just go in and out of AF and never get acclimated. What can be done for them?

Rate control. The first order of business is to get the heart rate under control to a resting rate between 60 and 90 beats per minute. This can be done with three different classes of drugs. Each of these drugs regulate the rate at which electrical signals travel between the fibrillating atrium and the main pumping chambers, the ventricles. The beta blockers, the calcium blockers and digoxin all are effective in regulating the heart beat, but some patients may need two or even three drugs for effective rate control. Beta blockers like metoprolol, bisoprolol, atenolol, and carvedilol may have some mild additional anti-arrhythmic effect as well as rate control, but some patients complain of tiredness on these drugs. Calcium blockers like diltiazem and occasionally verapamil are used to slow the heart rate, but some patients get swelling of the ankles and constipation from them. Digoxin is seldom used by itself because while it slows the resting heart rate, it may fail to control the heart rate during exercise. So digoxin is typically reserved as an add-on to a beta blocker or a calcium blocker.

Some patients’ heart rate cannot be controlled even with three drugs, and other patients are intolerant of the drugs. In these cases we consider a procedure called Pace and Ablate. A pacemaker is placed to provide a “floor” to the patient’s heart rate, so it cannot go below a minimum rate of for example, 60 beats per minute. Then a radio frequency catheter is inserted to permanently block (ablate) the electrical pathway between the atrium and the ventricle. The patient becomes dependent on the pacemaker to control the heart rate, and the atrial fibrillation no longer can excessively speed up the heart. When the patient exercises, the pacemaker will speed up the heart normally by tracking the heart’s natural pacemaker as long as the patient is in normal rhythm. When the patient is in AF, the pacemaker will speed up the heart using a sensor such as an accelerometer.

Rhythm Control. In patients who have been atrial fibrillation for less than a year, it’s been shown that attempts at restoring normal rhythm with cardioversion, anti-arrhythmic drugs or left atrial ablation leads to better outcomes than using rate control medicine and anticoagulation. This represents a new approach to atrial fibrillation vs what was practiced just a few years ago.

The anti arrhythmic drugs we have are not always effective and can have side effects. The standard-setting drug is amiodarone, but it is at best only 50-60% effective in preventing recurrent AF over the first year. All the other drugs we have are somewhat less effective. In terms of safety, amiodarone’s side effects are more frequent with high doses and longer duration of treatment. For AF, the dosing is usually quite low, around 100-200 mg per day so side effects are less common. Some patients on amiodarone develop over or underactive thyroid and excess skin sensitivity to sunlight. It’s very rare and unusual, but some patients get severe side effects in the lung, liver or nerves, which sometimes are fatal.

In patients whose hearts are completely normal except for the atrial fibrillation, drugs like flecainide, propafenone, sotalol, and others can be used with relative safety. Before these drugs are used, an echo and an evaluation for coronary heart disease should be done to make sure the heart is otherwise normal.

Left Atrial Ablation. It wasn’t that long ago that specialists in electrical diseases of the heart discovered that almost all atrial fibrillation comes from a previously inaccessible location in the left atrium. In the back of left atrium there are four pulmonary veins that deliver oxygen-rich blood from the lungs into the heart. The left atrium has a cuff of muscle tissue that extends a short distance into each of the four pulmonary veins, and those cuffs of muscle are where the atrial fibrillation comes from in almost every case.

Electrophysiologists have figured out that if the area around the pulmonary veins is electrically isolated from the rest of the left atrium in a procedure called ablation, that around 85% of patients will remain free of atrial fibrillation for at least a year.

Atrial fibrillation ablation has become easier, faster, more effective and safer with new tools that have been developed. In this procedure, a catheter is threaded up a vein from the groin, and it is passed through the wall between the right and left atrium. Once in the left atrium, extreme cold or radiofrequency energy are used to create a scar that encircles the pulmonary veins to isolate the source of the atrial fibrillation and allow normal rhythm to return.

Sometimes after an ablation there are gaps in the encircling scar that needs to be touched up in a second procedure if the AF returns.

Left atrial ablation is a wonderful procedure, but it is not without risks, some of which are life-threatening, like perforation of the heart, creation of a hole in the esophagus, stroke, and death. These are very infrequent, less than 1 in 200.

My atrial fibrillation doesn’t go away. What can be done?

Cardioversion. When a patient has his or her first episode of atrial fibrillation, and it doesn’t go away in a short time by itself, we call it persistent AF. We will often recommend that the patient be put to sleep for a couple of minutes and undergo electrical cardioversion. Cardioversion involves delivering an electrical shock, about half the intensity of the ones use for cardiac arrest, in order to synchronize the electrical signals of the atrium and restore normal rhythm. It is effective around 90% of the time, but about half of patients will go back into AF within a year. Results are best when the duration of the AF is short, and worse when it’s been present for over 6 months.

Cardioversion is generally considered quite safe. The risk of death is nearly zero, and the risk of stroke is very small since we insist on at least 3 weeks of blood thinners before the procedure to dissolve any clots. If the cardioversion must be done earlier than 3 weeks, a trans-esophageal echocardiogram is performed to inspect the left atrium to make sure there are no clots that could break loose and cause a stroke.

Leave it alone. If a patient has had atrial fibrillation for a long time, or has failed several cardioversions, and particularly if he or she has no symptoms, the better part of valor is to leave it alone and pursue anticoagulation and rate control.

How can I avoid recurrences of atrial fibrillation?

AF seems to come and go when it pleases. Patients are always trying to find a cause and effect for each episode, usually without real success. Still, there are some factors that appear to be closely associated with AF recurrences, and certain practices may cut down on your attacks:

- Avoid excess caffeine and any alcohol

- Don’t drink ice-cold liquids

- If you are overweight, lose (a lot of) weight